MAKING A LIFE, CREATING A WORLD WITH BARBARA EARL THOMAS

- Leilani Lewis

- Sep 25, 2024

- 8 min read

Updated: Sep 26, 2024

By Leilani Lewis

For as long as I’ve known Barbara Earl Thomas— sixteen years and counting—she has always said or done something that made me laugh. Her presence always draws people in with a perfect mix of humor, insight, and wisdom.

Barbara Earl Thomas is a renowned artist and cultural leader whose work has profoundly shaped Seattle’s creative landscape and extended far beyond. Her works are featured in prominent collections and shows in museums and galleries nationally, including Yale University and the Chrysler Museum of Art. Barbara has won the Washington State Governor’s Arts Award, among many others, and has been featured in national arts publications. Her work is dotted throughout the state, including the light-rail station on the I-90 lid, and Evergreen State College. She studied under Jacob Lawrence at the University of Washington and is a published author. Recounting Barbara’s achievements would fill volumes, but her enduring impact on art and culture speaks for itself. Barbara’s life–much like her art–is a testament to the power of storytelling, creation, and community.

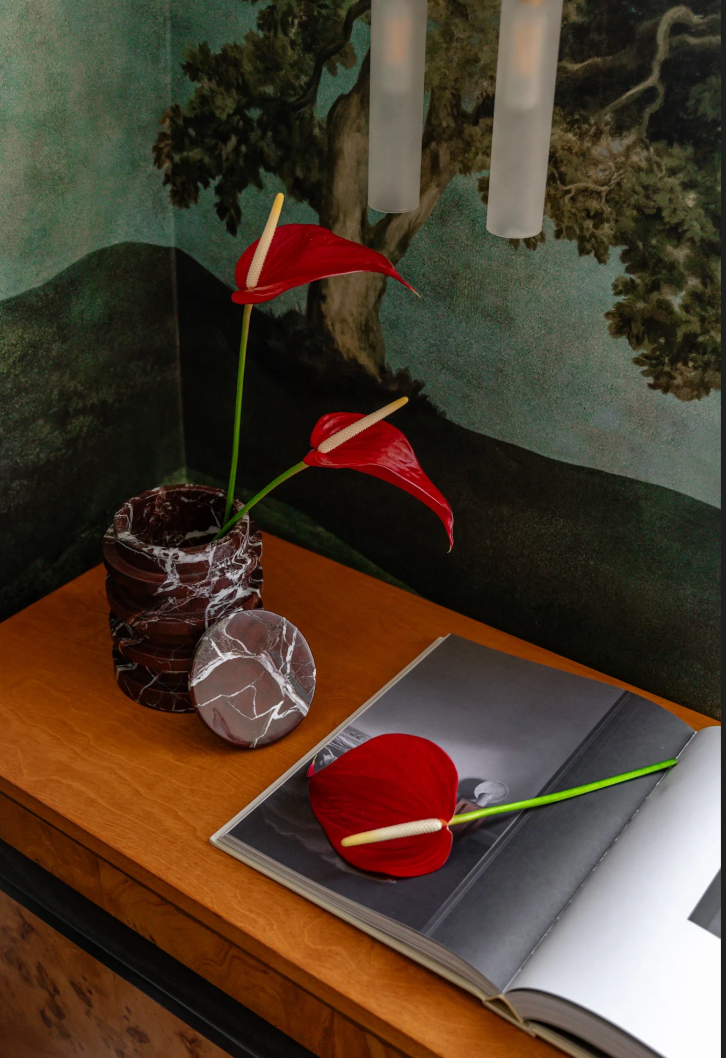

Barbara Earl Thomas; The Transformation Room. From The Illuminated Body, Arthur Ross Gallery, 2024. Photo: Eric Sucar.

So it’s no surprise that ARTE NOIR’s new maker space is named “The Barbara Earl Thomas Maker Space” in honor of her. The new space at ARTE NOIR Gallery, in the heart of Seattle’s Central District, is reserved for Black artists to use, without cost, to create their work.

I first met Barbara in 2007 while training to become a Northwest African American Museum docent. I did not know who Barbara Earl Thomas was when we met. At that time, I was still finding my place in the world—working to raise my daughter, develop a career, and find opportunities that connected me to the cultural work I was called to. So, I was nervous but eager, cold-calling museums and galleries to see if there were ways I could get involved (and get a paying gig). One cold evening in November, I was thrilled to attend an early docent training for the soon-to-open Northwest African American Museum when Barbara entered the room. She wore green overalls and a long grey cardigan, her short hair and brilliant smile immediately commanding attention. The subject of the training was the museum’s inaugural exhibition, Making a Life, Creating a World: Jacob Lawrence and James Washington Jr.

Her presence is magnetic, and she can make everything feel personal. For example, that night, the stories of Jacob Lawrence and James Washington Jr.’s works weren’t just part of distant art history but living, breathing narratives that we had a responsibility to carry forward. That night, she introduced herself to me so warmly that I couldn’t help but feel inspired and welcomed into a community where art and life were intertwined. Over the years, my friendship with Barbara has become one of my life's most cherished relationships.

Barbara Earl Thomas; A Bird in the Hand, Blown and sandblasted glass, 16" x 6.5", 2022. Courtesy of Barbara Earl Thomas, photo: Spike Mafford

MAKING A PLACE

Barbara’s memories of the Central District are infused with a deep sense of place that has shaped her identity and art. “The area has changed so much over the decades, but there’s still a presence here,” Barbara says. She is pleased to see efforts to preserve the Black community in the face of gentrification: “It’s odd to walk through the space and not see the same faces, but there’s a positive effort to acknowledge the change and make sure the Black community is still part of the story.”

Barbara’s roots in Seattle trace back to the 1940s, when her grandfather moved from rural Shreveport, Louisiana, to find work and buy a home for his family. His first stop was South Park, “He bought a little asbestos-shingled house surrounded by fertile farmland that he and my grandmother planted with greens and all manner of vegetables,” Barbara recalls.

“Making is thinking for me—it’s a way to sort through all the great and horrible things life has given me and examine the ways I’ve survived and the ways that I haven’t.”

When Barbara’s father returned from the Korean War, her family moved from Louisiana to Seattle’s Central District. “Black families, like mine of that era, headed for Seattle’s Central District to buy their first homes,” Barbara says. The Central District was one of the few places in the city where Black families could buy homes due to the redlining practices.” Barbara grew up on 21st and Union, just three blocks from Arte Noir Gallery. “My universe was within the blocks between Madison St. and just past Holy Names Academy, then from T.T. Minor Elementary to the top of Madrona.”

When Black families were able to move into the Central District during the 1940s and 50s, white families who previously lived in city centers moved out to the suburbs. “I remember the white flight,” Barbara recalls. “By the time I entered first grade at T.T. Minor Elementary in the mid-1950s, the few white families who remained kept their distance,” She explains. “Having lived through the 1960s era redlining and the struggle to integrate neighborhoods and schools outside the city core, it is ironic to think that maybe all we had to do was create a housing crisis to push us together out of sheer necessity.”

Barbara Earl Thomas; Girl With Flowers II, cut paper and hand-printed color backing, 40 x 26 in., 2022. From A Joyful Noise, Claire Oliver Gallery. Courtesy of Barbara Earl Thomas, photo: Spike Mafford.

CREATING A LIFE

Growing up in a household where making things was necessary, Barbara developed a deep connection to the act of creation from a young age. Her father, mother, and grandparents were all makers, constantly crafting solutions with their hands. “You needed something; you made it,” she says simply. “My father would draw up plans for the house, my mother sewed, and my grandparents made things with whatever they had on hand.”

This problem-solving mindset would later become central to Barbara’s art practice, in which the act of making is always a response to life’s challenges and opportunities. But her path to becoming an artist wasn’t immediate. Barbara initially attended the University of Washington in 1968, intending to study physical therapy. “It sounded like a good profession at the time,” she says. During UW’s push to diversify its student body in the late 1960s, Barbara, a UW staff member, was recruited to attend UW after a chance encounter in the U-District; she knew the opportunity could be significant.

New to the world of higher education, she knew she had to learn how to navigate the institution. “This was a big deal,” she explains, “but the only way I figured I could stay was to figure out how it worked. I was also focused on developing hard skills. At that time, I was part of a small group of students who had to work and go to school full-time.”

Despite the financial challenges of staying in school, Barbara’s dedication never wavered. She didn’t miss a single class during her undergraduate years, adhering to a strict discipline that would later become characteristic of her art practice. Eventually, she found her way to the university’s art department, where she received her BA and pursued her MFA. She studied under renowned artists Jacob Lawrence and Michael Spafford and graduated in 1977.

Barbara Earl Thomas; Holding Fire, 40 x 26 in., 2020. From Geography of Innocence, Seattle Art Museum, 2021–2022. Courtesy of Barbara Earl Thomas, photo: Spike Mafford.

MAKING A WORLD

“Making is thinking for me—it’s a way to sort through all the great and horrible things life has given me and examine the ways I’ve survived and the ways that I haven’t.”

Barbara Earl Thomas has worked across various mediums—from woodblock prints, acrylics, and oils to stained and blown glass—and her works consistently weave together elements of real life, lore, literature, and the natural world, often exploding with flora, fauna, and little creatures like birds and snakes. One of her signature mediums, however, is cut paper. Barbara uses this technique to create large-scale, immersive environments she calls “illuminated scenography,” inviting viewers to step inside and experience the interplay of light, shadows, and stories. These installations, made from miles of meticulously cut Tyvek paper, are a statement of her dedication to craft and attention to detail, transforming space and narrative into a singular experience.

Barbara’s art is also a conduit for deeper connection, transcending the creation of mere objects or images. She captures everyday beauty's natural rhythms and patterns through her work, blending concrete reality with the fantastical. "My work is about reacting to the moment you’re in," Barbara explains. "Living is making sense of your everyday, and we make stories out of our lives."

Her artistic practice deeply reflects this philosophy, especially in her portraits of loved ones and community figures, where storytelling becomes a medium for understanding and celebrating life.“I’m interested in how the work connects people. The story includes me when I make a piece, but it’s also about the people who show up and add their own stories to the work.”

Her portraits glow with negative space illuminated by color to draw out the details of her subject. Using the interplay of light, shadow, and color, these portraits form a tapestry of connection that resonates with the community it celebrates.

Attending Barbara Earl Thomas’s 2021 solo exhibit Geography of Innocence, at the Seattle Art Museum with my mom, I had the honor of viewing a portrait she based on a photo of me. As we stood before Holding Fire, tears filled my mom’s eyes as she saw my likeness in Barbara’s work. This moment stays with me—witnessing my mother’s pride and our shared elation, knowing that Barbara’s work was celebrated in such a prestigious space. Just months later, my mother passed away, making that moment of joyful connection with Barbara’s art even more meaningful.

Author Leilani Lewis with her mother, Evelyn, at Geography of Innocence, Seattle Art Museum. Photos courtesy of the author.

CREATING THE SPACE FOR STORIES

To anyone stepping into the new maker space at ARTE NOIR, named in honor of Barbara Earl Thomas, know that this place carries her spirit of creativity, joy, purpose, and integrity. Let Barbara’s legacy inspire you as you work—live with intention, create with discipline, and infuse your art with the stories that matter most to you.

ARTE NOIR's Barbara Earl Thomas Maker Space is set to open before the end of this year so keep an eye out for the official date!

Barbara Earl Thomas; Illuminated Room as part of Geography of Innocence, Seattle Art Museum, 2020.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Leilani Lewis, photo by Eli Branch

Leilani Lewis is an award-winning arts leader and seasoned Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Belonging (DEIB) practitioner based in Seattle. She has been honored with the 2017 Mayor's Arts Award for Emerging Leader and the Marylynn Batt Dunn Award for Excellence from the University of Washington. With over 15 years of experience, Leilani’s work bridges the creative sector and higher education, where she is known for her commitment to service, fostering community engagement, and building innovative partnerships.

As the Senior Director of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion for the University of Washington Advancement, Leilani is a visionary leader whose transformative DEIB frameworks have been embraced by institutions nationwide, affirming her status as a thought leader in the field.

Leilani is a sought-after speaker at national conferences and has been deeply involved in the arts community, serving on various boards, producing programs, and consulting across the Seattle area. She is also the co-founder of Black Women Write Seattle, a group dedicated to supporting Black women on their journey to publication. Leilani holds a postgraduate degree from Seattle University and is a certified DEIB practitioner.

Comments